The Unexpected U.S. Election of 2016

In 2016, Donald Trump was elected president of the United States. That a controversial billionaire celebrity with no prior political experience could win the election sent academics and commentators from all along the political spectrum into a state of panic and confusion. Most polling organizations showed Hillary Clinton with a consistent lead, so pundits did not expect Trump’s win, and dozens of news articles and editorials emerged asking how his win could have happened—and how the experts could have been so wrong.[1]

While the majority of mainstream media outlets did not predict a Trump triumph, it is unfair to say that no one foresaw it. In February, political science professor Helmut Norpoth predicted a 97 percent chance of a Trump win using his own statistical polling model.[2] In April, historian Allan Lichtman, who has accurately predicted every presidential win since 1984, called a Trump win “certain.”[3] In July, Michael Moore argued that Trump would win because of the influence of the Rust Belt working class and the unpopularity of Clinton.[4] And while Clinton was the favored candidate, the large polling conglomerate FiveThirtyEight still had Trump’s chance of winning at 29 percent.[5]

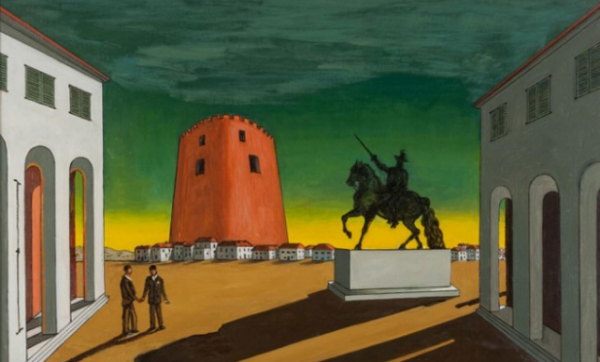

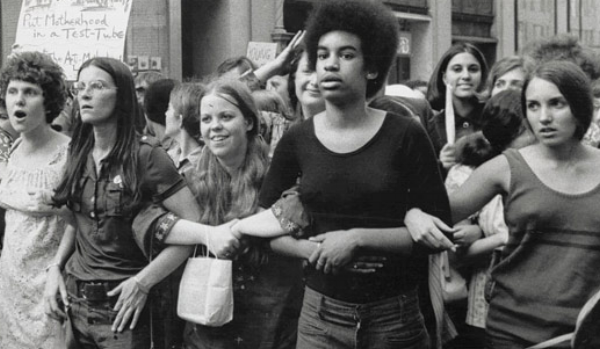

2016 Electoral College Map, Adjusted for Population (Mark Newman)

Despite their warnings, these figures remained outliers, and Trump’s victory shocked political analysts and the mainstream media. The unexpected win was the culmination of a growing divide in American culture between socially liberal coastal elites and the generally socially conservative working class. Middle America became disillusioned with establishment elites, and liberal professionals underestimated working-class resentment. What resulted was the rise of two unlikely outsider candidates: Bernie Sanders, a self-described “socialist” who ran against Clinton in the Democratic primaries, and Trump, who began as the least-favored Republican candidate yet won Republican approval bit-by-bit over the course of the election.[6] Even though Sanders and Trump were on opposite ends of the political spectrum, 1 in 10 Sanders voters ended up voting for Trump, demonstrating that the 2016 election was not so much about party lines, but something deeper.[7]

It was a deeper cultural divide that ultimately culminated in a Trump presidency. Yet, this divide is not a new phenomenon. Rather, it is the result of a growing political polarization in American culture that began in the 1970s and 1980s. The contemporary media scrambled to figure out what went wrong in the 2016 election, blaming everything from Russian interference to social media echo chambers.[8] However, analysts would have fared better with a broader historical view that looked back almost half a century on the roots of this political polarization in the United States.

The Disillusioned Seventies

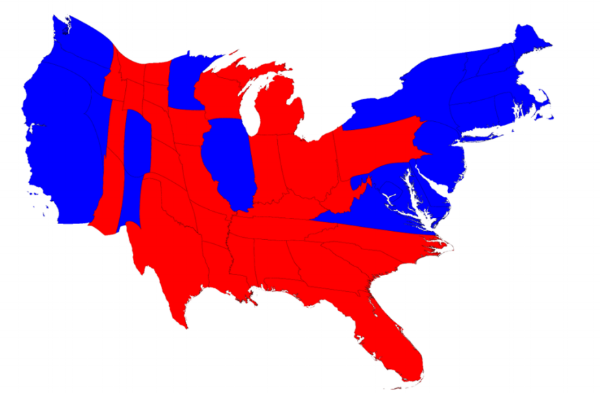

The Seventies marked a great shift in American culture. The postwar economic boom died, and the optimistic dream of the Sixties was in decline. A series of culturally significant moments represented this decay. In 1969, the Manson Family committed their infamous murders, including that of actress Sharon Tate.[9] These crimes, coupled with the increase in hard drug use, gave the hippie scene a gloomier tone. Later that year, at the Altamont Free Concert, the Hells Angels, who were hired by the Rolling Stones as security guards, beat many members of the audience, and stabbed Meredith Hunter to death.[10] Whereas Woodstock represented the peace-and-love Sixties so prevalent in popular memory, Altamont represented the darker side, or, as historian Mark Lytle noted, it became “a symbol for the end of the Woodstock Nation.”[11] In 1972, Hunter S. Thompson published Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, which reflected on failures of the counterculture movement.[12] Thompson’s book set the tone for the Seventies malaise, and as cultural critic Christopher Lehmann-Haupt put it, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas “picks up where Norman Mailer’s An American Dream left off and explores what Tom Wolfe left out.”[13]

Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas: A Savage Journey to the Heart of the American Dream

The disillusionment with the New Left and the counterculture movements of the 1960s paved the way for Richard Nixon’s capitalizing on the notion of the “Silent Majority.” Nixon strategically divided Americans into two groups: intellectuals, freaks, and liberals on one side and the silent patriotic citizens who were concerned about the erosion of social mores on the other. Nixon claimed that these “Forgotten Americans” were the “unsung heroes of the nation and the underserving victims of the liberal War on Poverty, the military stalemate in Vietnam, the militancy of the Black Power movement, and the disorder in the cities and on the college campuses.”[14] Republican politicians used the Silent Majority language frequently during the 1970s and 1980s, especially during Ronald Reagan’s era, and the language unsurprisingly resurfaced during Donald Trump’s presidential campaign, with Trump stating that the “Silent Majority is back, and we’re going to take our country back!”[15]

On the economic front, the Seventies indicated a time when postwar financial security was replaced with stagflation: high unemployment rates, high inflation, and slow economic growth.[16] During the early 1970s, unemployment hovered around 5 percent, but by the mid-1970s and early 1980s, unemployment never fell below 6 percent and went as high as 9 percent.[17] Inflation skyrocketed as well. By 1974, inflation rose to 11 percent, levels that had not been reached since the 1940s. By 1980, inflation had climbed to over 13 percent.[18] Additionally, the 1970s experienced the deepest recession since World War II up to that time, poor economic productivity, trade deficits, and a 20 percent jump in oil prices.[19] This combination of economic factors placed the Seventies in stark contrast with the economic boom people had become accustomed to in prior decades.

The bleak economic situation in the 1970s hit the working class hardest. The implementation of neoliberal economic policies, such as privatization and deregulation, contributed to the widening gap between the wealthy and the poor, and the gradual shrinking of the middle class. American manufacturing moved abroad, and the beginnings of a technological revolution threatened the stability of manufacturing jobs altogether.[20] The working class especially felt the crunch with the decline of union membership. With rising competition from overseas manufacturing and an increase in anti-union policies to discourage workers from organizing and from making demands (especially through strikes), union membership started its decline in the late-1970s, ultimately dropping from 35 percent of the private sector to a mere 6 percent today.[21] Workers’ wages stagnated, even as the GDP began to rise again in the 1980s and 1990s. Productivity climbed and investment income rose, while inflation-adjusted wages barely increased at all, leaving the working class struggling to keep up with the rising costs of living.[22]

The rapid decline in union membership and the deregulation of industry contributed to a steady rise in income inequality. The postwar 1950s and 1960s maintained a healthier middle class and wealth distribution. However, beginning in the 1970s, wealth became more heavily concentrated at the top, leaving the middle class lagging behind. In other words, there was a strong correlation between the decline of unions and the rise of neoliberal economic policies in the 1970s and 1980s with growing inequality and lack of upward mobility for the middle class.[23]

Unemployment Line in New York (1974)

This amalgam of economic problems played a significant role in the social and political climate of the 1970s and 1980s. With increased economic inequality came an upsurge in political polarization and a lack of confidence in the effectiveness of politicians. In a Princeton University study conducted in 2015, a group of political scientists and economists determined that the growing gap between the wealthy and the poor contributes to the ideological gap between the Republican and Democratic parties.[24] This observation echoes other studies that demonstrate similar trends. For instance, in the 1980s, less than half of people polled felt a strong animosity towards those of the opposite political party; yet, by 2012, up to 80 percent of those polled felt extremely cold toward those in the other party.[25] One of the key reasons for this growing political polarization is economic: the working class has continually felt abandoned by the Democratic Party since it began adopting neoliberal policies tied to Wall Street and global markets, leaving the American working class in the dust. This situation contributed to the notion that the professional class has become increasingly out of touch with regular Americans, and that the Democrats are no longer the party of the people.

The Conservative Shift and the Culture Wars

While the economy plays a crucial role in political polarization, it does not fully explain the growing division in American politics today. For that, it is necessary to examine the subtler aspects of American culture. The roots of these contemporary divisions go back to the 1970s and 1980s, during which sociologists and political scientists see the beginnings of what would later be called the “culture wars.” Even though the New Left was not ultimately successful in their anti-war dreams, its Civil Rights successes stirred up cultural tensions that would come to the surface over the next few decades.

The culture wars have their roots with the rise of neoconservatism in the 1970s. The main proponents of neoconservatism were, early on, members of the New York intellectuals who shifted from the anti-Stalinist left to a more hawkish stance on foreign policy. Their position was both political, becoming dissatisfied with the Democratic Party’s pacifist position in Vietnam, and cultural, becoming fearful of the postmodern extremes that the counterculture had taken. In his essay, “Beyond Modernism, Beyond Self,” Daniel Bell discusses the growing fear of postmodern thinking in the post-Sixties era. He argues that the postmodernists have “pressed the logic of modernism toward its most radical theoretical conclusions” and, in doing so, created a Dionysian narcissistic pop culture.[26] Bell hoped that the solution would be a return to more traditional institutions, and other intellectuals shared this nostalgic reactionaryism.

Irving Kristol emerged as one of the key architects of neoconservatism in its early stages. In 1979, Esquire featured Kristol on the cover, and the feature article outlined neoconservatism as the “powerful new force in America.”[27] Kristol, along with William F. Buckley and Norman Podhoretz, penned the ideas of the neoconservative movement in magazines such as Commentary, Encounter, and National Review. By the 1980s, these magazines boasted their highest readership since their beginnings, bringing neoconservative ideas to the wider public.[28]

In the 1970s, the feminist movement gained considerable ground, prompting the right to react against a perceived decline in family values. Birth control and abortion rights, along with efforts for equal pay legislation, meant that the postwar nuclear family model had been upended. The feminist movement achieved a handful of successes in the 1970s and 1980s, such as Roe v. Wade, which made abortion legal; Title IX, which prohibited sex discrimination in educational programs; the Pregnancy Discrimination Act, which banned employment discrimination against pregnant women; and Kirchberg v. Feenstra, which stated that “head and master” laws were unconstitutional.[29]

Women's Strike for Equality (1970)

These victories for feminism created a backlash from social conservatives. Roe v. Wade was a setback for anti-abortion activists, but conservative groups would continue to push for legislation that chipped away at the law. One success for the pro-life group was the passing of the Hyde Amendment that prohibited the use of federal funds for abortion services. The abortion wars would continue to be a hot button issue and contribute to the widening cultural divide. As historian Bradford Martin notes, “The story of the 1980s abortion wars emerges as one in which feminist activists battled mightily, amid limited political opportunity and against the conservative tide, to retain the hard-won gains of the 1960s and 1970s.”[30] To combat these feminist achievements, a number of conservative women’s institutions popped up during this time, most notably Concerned Women for America (CWA), whose goal was an “anti-feminist” approach to women’s issues and the promotion of “Biblical values.”[31]

The feminism issue bled into education as well. Conservatives worried that students were being indoctrinated with liberal ideas, thus causing a wide mistrust of the education system altogether. In 1982, philosopher and classicist Allan Bloom wrote a cutting essay in the National Review that critiqued the modern university system. In “Our Listless Universities,” Bloom argued that the ethos of the Sixties—ideas such as feminism, liberalism, postmodernism, and relativism—destroyed the intellectual goals of the college setting.[32] Feminism, for Bloom, was a chief sin, infecting students’ minds with relativistic jargon and degrading the traditional humanities education by claiming that “all old books are no longer relevant because their authors were sexists.”[33]

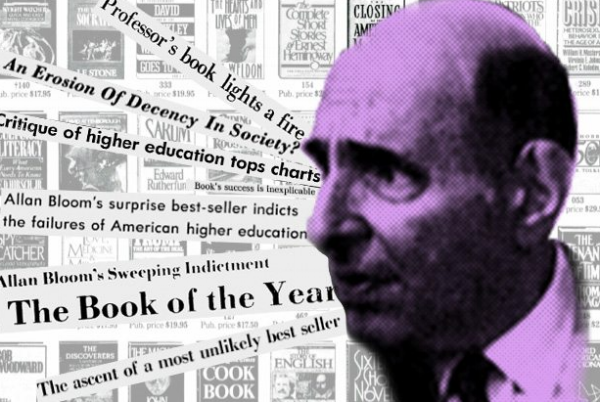

In 1987, Bloom’s thesis developed into a bestselling yet controversial book, The Closing of the American Mind, which expanded on his essay and argued that “poor education has impoverished” the souls of college students.[34] While Bloom never claimed to be a conservative himself, his ideas surely fit within the conservative attitude of the 1980s. Roger Kimball, editor of the conservative literary magazine New Criterion, wrote that Bloom’s work was “essential reading for anyone concerned with the state of liberal education in this society” and that students had become “committed to an ethic of cultural relativism.”[35] Kimball would later write two related books in the 1990s: Tenured Radicals and Rape of the Masters, both of which pointed to the growing number of liberal professors in the universities who, according to Kimball, sought to subvert the traditional humanities education with leftist ideologies. Kimball felt these professors were creating a new elitist class who were difficult to compete with because of their educational credentials.[36]

These criticisms of the American university would continue to grow, and, by 2016, debates about the effectiveness of the education system became strongly divided between conservatives, who felt that colleges were overrun by race, gender, and queer studies, and liberals, who felt that conservatives only wished to preserve the ideas of dead white men. From the left’s view, education should correct history’s oversight of oppressed groups. From the right’s perspective, the left spent too much time with politically-correct language policing. These debates featured heavily in the 2016 election, with both sides fearful of what education had become and what education in the United States should be.

Allan Bloom

Conservative concerns about abortion, feminism, and the liberal university were often tied to the upsurge of the Religious Right in the United States during the 1970s and 1980s. Gaining its footing in the Reagan era, the Religious Right’s connection to Republican politics has steadily increased over the years.[37] Much of the Religious Right’s ascent can be traced back to evangelical leader Jerry Falwell. As television displaced radio, televangelist preachers became household names. When Falwell’s popularity grew, he began to mix his religious convictions with his political ones. In 1976, Falwell embarked on a series of “I Love America” rallies to raise awareness about what Falwell perceived as the growing problem of the nation’s moral decay.[38] Asserting that Christians should mix their morality with their politics, Falwell held up the Bible to his audience and proclaimed, “If a man stands by this book, vote for him. If he doesn’t, don’t.”[39] By 1978, Falwell’s message gathered more support, and an article in Esquire called him the “next Billy Graham” and said that he would be “the first preacher to become a political leader.”[40] In 1979, Falwell formalized his goals by founding the Moral Majority, an organization that tied the Religious Right with the Republican Party.[41] The Moral Majority sought to promote prayer in schools, ban abortions and homosexuality, and oppose liberal media outlets—all while supporting politicians who abided by these standards and supported these ideas through legislative measures.[42]

By the 1990s, the left and the right continued to polarize, each more stringently aligning with their (or what was perceived to be their) side. The culture wars that began in the 1970s and 1980s had dramatically realigned the face of American society. No more were people divided by the strict party lines of the past, but instead, cultural differences had turned political, and individual issues became contentious battlegrounds. In 1991, sociologist James Hunter popularized the term “culture wars” in his book Culture Wars: The Struggle to Define America. In this work, he argued that the conventional dividing lines no longer applied, but rather, differences take shape in the form of traditionalism versus progressivism, or liberation versus equality.[43] This new quarrel becomes dangerous, says Hunter, because each side becomes rigid and less open to nuance. Hunter notes that the reason for this is that “each side characterizes their rivals as extremists outside the mainstream” and that “each ardently believes that the other embodies and expresses an aggressive program of social, political, and religious intolerance.”[44] Thus, the forming political polarization was no longer simply one party pitted against the other, but citizens were becoming more polarized about special interest issues related to family, education, censorship, law, and the media—all of which were manipulated by establishment politicians who could no longer be trusted to have the people’s best interests in mind.

Culture Wars

This resistance to establishment politics led Pat Buchanan to challenge incumbent President George H. W. Bush in 1992 on a platform that opposed immigration, multiculturalism, abortion, gay rights, and similar social issues that seemed to contribute to, from Buchanan’s perspective, America’s moral decay.[45] He later supported Bush against Bill Clinton’s run for the presidency, reviving old tropes about the liberalism of the Sixties. In his speech at the Republican National Convention in 1992, Buchanan said that there was an ongoing culture war “for the soul of America” and that a Clinton win would “impose on America abortion on demand, a litmus test for the Supreme Court, homosexual rights, discrimination against religious schools, women in combat.”[46] At this point, modern political polarization had taken root and would only continue to grow.

Political Polarization Moves in the Twenty-First Century

In 1989, political scientist Francis Fukuyama’s essay “The End of History?” suggested that the end of the Cold War marked “the end point of mankind’s ideological evolution and the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government.”[47] Not everyone was so optimistic, however. In 1992, Benjamin Barber’s article “Jihad vs. McWorld” criticized neoliberalism, suggesting that corporate globalization would likely lead to an undemocratic international tribalism.[48] A year later, Samuel Huntington’s essay “The Clash of Civilizations” argued that, counter to Fukuyama’s claims, post-Cold War conflict would be cultural rather than political, specifically culminating in tensions between Islam and the West.[49] Fukuyama’s naiveté became evident in 2001 with the September 11th attacks on the World Trade Center, prompting the war in Iraq and accelerating the war on terror.[50]

Rather than the globe reaching some kind of liberal world order, the 2000s brought a new host of problems: terrorist attacks, the dot-com burst, the housing crisis, bank bailouts, and a host of economic and social problems associated with the rise in globalization and unregulated international markets. Meanwhile, wealth inequality continues to grow. In 2017, Oxfam found that the eight wealthiest people in the world, six of whom are Americans, own as much wealth as half of the entire human population, or about 3.8 billion people.[51] Additionally, identity politics continue to divide Americans in a visceral way, and ideological differences are increasingly shaped by tribal behavior rather than through reasoned debate.[52] Social media causes people to both consciously and unconsciously filter out information that contradicts their views, resulting in a lack of viewpoint diversity and a homogenization of political ideas.[53]

Income inequality has been rising since the 1970s.

The current daunting state of political polarization can be traced back to the 1970s and 1980s when these cultural differences were just getting formed. Historians tend to avoid taking lessons from history, but if one considers the larger patterns of cultural divisions in the United States, looking back at this earlier era may offer some clues. One fact is certain: historians and political scientists can no longer rely on the standard party line model to explain the country’s split. The traditional formula does not square well in contemporary times. Instead, analyses on contemporary political polarization should take into consideration the cultural roots that have since bloomed into a larger tree. By examining the beginnings, it may be possible to reclaim some common political threads.

Footnotes:

[1] Jim Rutenberg, “News Media Again Misreads Complex Pulse of the Nation,” New York Times, November 9, 2016, 15.

[2] Christopher Cameron, “Political Science Professor Forecasts Trump as General Election Winner,” The Statesman, February 23, 2016.

[3] Peter W. Stevenson, “Trump Is Headed for a Win, Says Professor Who Has Predicted 30 Years of Presidential Outcomes Correctly,” Washington Post, September 23, 2016.

[4] Michael Moore, “Five Reasons Why Trump Will Win,” Michael Moore, July, 2016.

[5] Nate Silver, “Why FiveThirtyEight Gave Trump A Better Chance Than Almost Anyone Else,” FiveThirtyEight, November 11, 2016.

[6] Philip Bump, “Bernie Sanders Is an Avowed Socialist. 52 Percent of Democrats Are OK with That,” Washington Post, April 29, 2015; Tom Rogan, “Meet the Candidates: 20 Republicans Who Are Vying to Run for President in 2016,” The Telegraph, May 6, 2015.

[7] Danielle Kurtzleben, “Here’s How Many Bernie Sanders Supporters Ultimately Voted for Trump,” National Public Radio, August 24, 2017.

[8] Scott Shane and Mark Mazzetti, “Inside a 3-Year Russian Campaign to Influence U.S. Voters,” New York Times, February 16, 2018.

[9] Vincent Bugliosi and Curt Gentry, Helter Skelter: The True Story of the Manson Murders (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1974), 21–57.

[10] Gimme Shelter, directed by Albert Maysles, David Maysles, and Charlotte Zwerin (New York: Maysles Films, 1970), film.

[11] Mark Hamilton Lytle, America’s Uncivil Wars: The Sixties Era from Elvis to the Fall of Richard Nixon (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006), 336.

[12] Hunter S. Thompson, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas: A Savage Journey to the Heart of the American Dream (New York: Random House, 1972), passim.

[13] Christopher Lehmann-Haupt, “Book of the Times,” New York Times, June 22, 1972, 37.

[14] Matthew D. Lassiter, The Silent Majority: Suburban Politics in the Sunbelt South (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2006), 232.

[15] Nicholas Fandos, “Trump Defiantly Rallies a New ‘Silent Majority’ in a Visit to a Border State,” New York Times, July 11, 2015, 20.

[16] Thomas Borstelmann, The 1970s: A New Global History from Civil Rights to Economic Inequality (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012), 55.

[17] Edward D. Berkowitz, Something Happened: A Political and Cultural Overview of the Seventies (New York: Columbia University Press, 2006), 55.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Judith Stein, Pivotal Decade: How the United States Traded Factories for Finance in the Seventies (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010), 11.

[20] Philip Jenkins, Decade of Nightmares: The End of the Sixties and the Making of Eighties America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006), 65.

[21] Jefferson Cowie, Stayin’ Alive: The 1970s and the Last Days of the Working Class (New York: The New Press, 2010), 311.

[22] Jacob Kornbluth, Inequality for All (San Francisco: 72 Productions, 2013), film.

[23] Ross Eisenbrey and Colin Gordon, “As Unions Decline, Inequality Rises,” Economic Policy Institute, June 6, 2012.

[24] Nolan McCarty, John Voorheis, and Boris Shor, “Unequal Incomes, Ideology and Gridlock: How Rising Inequality Increases Political Polarization,” Social Science Research Network (2015): 2–10.

[25] Ken Stern, Republican Like Me: How I Left the Liberal Bubble and Learned to Love the Right (New York: Harper Collins Publishers, 2017), 6.

[26] Daniel Bell, “Beyond Modernism, Beyond Self,” in The Winding Passage: Sociological Essays and Journeys (London: Routledge, 1980, originally published in 1977), 302.

[27] Geoffrey Norman, “The Godfather of Neoconservatism (And His Family),” Esquire, February 13, 1979, 36–37.

[28] Andrew Hartman, A War for the Soul of America: A History of the Culture Wars (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015), 47–53.

[29] Estelle Freedman, No Turning Back: The History of Feminism and the Future of Women (New York: Random House, 2002), 237–238.

[30] Bradford Martin, The Other Eighties: A Secret History of America in the Age of Reagan (New York: Hill and Wang, 2012), 169.

[31] Ronnee Schreiber, Righting Feminism: Conservative Women and American Politics (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 26.

[32] Allan Bloom, “Our Listless Universities,” The National Review, December 10, 1982, 29–33.

[33] Ibid., 35.

[34] Allan Bloom, The Closing of the American Mind: How Higher Education Has Failed Democracy and Impoverished the Souls of Today’s Students (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1987), 156.

[35] Roger Kimball, “The Grooves of Ignorance,” New York Times, April 5, 1987, 7.

[36] Hartman, A War for the Soul of America, 249.

[37] “Trends in Party Identification of Religious Groups,” Pew Research Center, February 2, 2012.

[38] Dominic Sandbrook, Mad as Hell: The Crisis of the 1970s and the Rise of the Populist Right (New York: First Anchor Books, 2011), 344.

[39] Peter Applebome, “Jerry Falwell, Leading U.S. Religious Conservative, Dies at 73,” New York Times, May 15, 2007.

[40] Mary Murphy, “The Next Billy Graham,” Esquire, October 10, 1978, 25.

[41] Daniel T. Rodgers, Age of Fracture (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2011), 168.

[42] Robert C. Liebman, and Robert Wuthnow. The New Christian Right (New York: Aldine Publishing Company, 1983), 55–57.

[43] James Davison Hunter, Culture Wars: The Struggle to Define America (New York: Basic Books, 1991), 11.

[44] Ibid., 148.

[45] Richard Jensen, “The Culture Wars, 1965–1995: A Historian’s Map,” Journal of Social History 29, no. 1 (1995): 21.

[46] Patrick J. Buchanan, “1992 Republican National Convention Speech,” Republican National Convention, August 17, 1992.

[47] Francis Fukuyama, “The End of History?” The National Interest, no. 16 (1989): 4.

[48] Benjamin R. Barber, “Jihad vs. McWorld,” The Atlantic, March, 1992, 53–63.

[49] Samuel P. Huntington, “The Clash of Civilizations?” Foreign Affairs 72, no. 3 (1993): 22–49.

[50] George W. Bush, “Remarks by the President Upon Arrival,” White House Press Release, September 16, 2001.

[51] Gerry Mullany, “World’s 8 Richest Have as Much Wealth as Bottom Half, Oxfam Says,” New York Times, January 16, 2017.

[52] Jonathan Haidt, The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion (New York: Pantheon Books, 2012), 319–312.

[53] Hunter Cohen, “Social Media Echo Chambers Increase Political Polarization,” Medium, March 1, 2017.

By Shalon van Tine

(Cover photo credit: Brian Stauffer)